“Foreign lands never yield their secrets to a traveller. The best they offer are tantalising snippets, just enough to inflame the imagination. The secrets they do reveal are your own – the ones you have kept from yourself. And this is reason enough to travel, to leave home.”

― Graeme Sparkes

This is a throw-back post, and one I started some time ago and am just now getting to finish up. So far, my year 2015 has turned out to be nothing like I expected it would be at the start of the year. It has been a whirlwind of unforeseen activity and circumstances. I expected at this point to be looking for/recently begun some sort of post-baccalaureate work. Instead I find myself still unfinished with school and once again living in the Middle East. While there is little I can say at this point about what I’m currently doing, I would like to go back and record, for my own sake if no one else’s, some of my adventures in Qatar this past March.

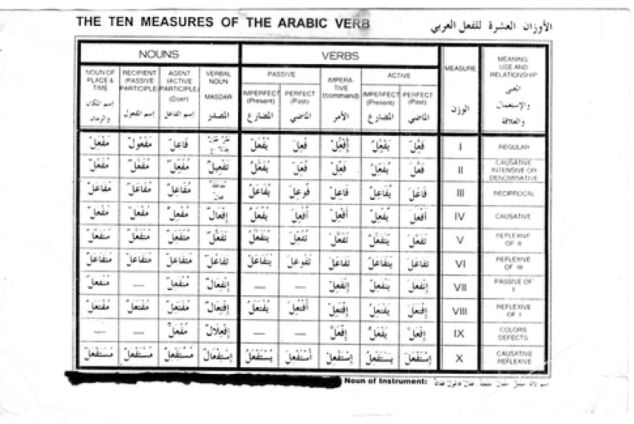

Street view of downtown Doha

So I ended up in Qatar for about three weeks. I was there to work as an interpreter. A group of Americans were there to do some training with a group of Qatari counterparts, and I was there to make sure they could communicate with one another. I was glad to be there, to put my language skills and experiences to use after all my years of study. I was also happy to be exposed to a new Arab country and culture. I had never really been around speakers of the Gulf dialect of Arabic, which at times certainly posed a challenge for me as an interpreter. I had also never really seen what I guess I kind of see as “how the other half lives” in the Arab world. All of my previous experiences in the Middle East had been in relatively poor, developing nations. Qatar, in contrast, is one of the wealthiest nations in the world per capita. It’s a tiny little peninsula jutting off the Arabian peninsula into the Persian Gulf, but it has immense oil resources at its disposal. If you’re a native Qatari citizen you basically have it made, materially speaking, your whole life. Of course all this wealth is a relatively recent development, and most of my experience in Qatar was characterized by this fascinating dichotomous clash between very conservative desert culture and the progressive development and opulence afforded by wealth.

Take a look at this picture. This is a photo I took beside the swimming pool of the hotel I stayed at while I was in Qatar. Yup. I got paid to live here for three weeks. I don’t say that in a braggy sort of way. I say that… well, for a couple of reasons really. First, I say that because lately I often find myself wondering to myself, “What is my life?” The fact that I was getting paid to stay here sure made me wonder that. Secondly, I wanted to point out the hotel I was staying at because in all honesty it was a fairly modest sort of place to stay in Doha. It’s all relative, right?

So there honestly isn’t much to say about the actual work I was doing. Translating powerpoint presentations and individual conversations was challenging but doable. Most of it was fairly technical so there was a bit of a learning curve, but by the time we left I was really in the groove. So much so in fact that for a few days after I returned to the States anytime someone was saying something around me I would be unconsciously forming the Arabic translation in my head as if I was shortly going to have to relay their message to someone who didn’t understand them. Anyway, the point I was trying to make when I started this paragraph is that the actual day-to-day work was pretty monotonous and bears little mentioning. Happily for me (and to the chagrin of many of the Americans I was working with), Qataris aren’t particularly interested in an American eight-hour workday, so I had a fair amount of free time to get out and explore what I could of Qatar.

A Pedestrian Crossing sign. Notice anything different about Qatari pedestrians?

I think it’s interesting that in fact the majority of the people who live in Qatar are not Qataris. As strange as it may sound, native Qataris are in fact a minority in their own country. There are loads of foreign workers. While the actual Qataris are extremely wealthy, there is shocking poverty in the country. Many of you have maybe heard of the scandals surrounding the 2022 World Cup, which is supposed to be held in Qatar. So far hundreds (if not thousands) of foreign workers have died constructing the stadiums and other building projects related to hosting the World Cup because of the extremely adverse working conditions they’re forced into. From what I’ve read it really does sound pretty horrible. Many of the workers’ only legal grounds for being in the country is to work and employers take advantage of them in terrible ways, confiscating their passports, forcing them to work long hours in unbearable heat, housing them in tiny, crowded hovels, and then often paying them ridiculously low wages – if they pay them at all. It’s basically slavery. The following picture is one I took initially because I found it humorous that a sign reading “men at work” was posted next to a group of workers sitting and doing nothing, but then I realized and was humbled by the thought of just what life is probably like for those sitting men.

My experience in Qatar was I think unique in the sense that most people visiting the country have relatively few interactions with the native Qataris (seeing as how they’re the minority and often view themselves as being above most others), but because I was there as an Arabic interpreter I actually spent more time with Qataris than anyone else. It really was interesting to see what wealthy Arabs do with themselves. One of the Americans I was with made the comparison between them and the Beverly Hillbillies. While such an unflattering comparison is one I hesitate to agree with, there really is a lot of conservative desert culture that transfers over into their wealthy lifestyle. One night, we were invited to join one of our Qatari friends at his desert ranch on the other side of the country (which takes about an hour to drive across). Just outside his nice, modern home was a beit sha’r (literally translates as “house of hair” from Arabic, in reference to the woven wool fabric it’s made of):

All of the Qataris of course wore their traditional white jalabiyya and either white or red-and-white checkered ghatta:

This particular experience left me with some interesting thoughts about what a rather traditional, wealthy Arab household is like, but I think even now I haven’t been able to sufficiently digest and understand things well enough to offer my ideas. I’ll suffice it to say that it was overall a pleasant and enjoyable evening out in the desert.

Before the dinner though, we took a bit of a drive out into the desert and saw some interesting things. The oryx, or maha, is I believe seen as something of a national symbol for Qatar, and there is a nature preserve near the home of our host, so we got to see some.

We also drove out to a traditional desert fortress. This particular one is a recently built recreation, but it was made following traditional designs and was built using only tools and materials that were available back in the day.

The desert really is a remarkable place. I’ve said that before and had people look at me like I was crazy. Call me a naive romantic if you want, something about the austere beauty of the desert and isolated places like this fortress just seem to tickle my soul.

Which reminds me of a quote I’m fond of from Annie Caulfield: “It takes time to see the desert; you have to keep looking at it. When you’ve looked long enough, you realize the blank wastes of sand and rock are teeming with life. Just as you can keep looking at a person and suddenly realize that the way you see them has completely changed: from being a stranger, they’ve gradually revealed themselves as someone with a wealth of complexities and surprising subtleties that you’re growing to love. ”

One of the more unique experiences I had was when one of the Qataris I was working with took us to the races after work one day. No, not stock-car races, or horse races, or even greyhound races. I’m talking about camel races. This guy was very passionate about his hobby of breeding, raising, training, and racing camels. Yes, that’s quite an expensive hobby. Yes, this guy, like the majority of Qataris, is filthy rich (he married his third wife while I was there. Practicing polygamy is allowed in Islam so long as the man is able to treat all of his wives equally, which generally means that only fairly wealthy men tend to have multiple wives). Before going to the track he took us to his camel ranch to show off the finest of camel specimens (yes, I say that facetiously, because, as I’ve said before, camels are goofy, bizarre animals).

Some of his young, thoroughbred camels. Each of these animals is worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Watch out, they spit!

The proud owner

We then got to witness first-hand an actual camel race. It was certainly unique. If you’re imagining a circular track with a grandstand for an audience to sit in and watch, you’re totally off. Camel races cover something like 12 kilometers and it’s all just a straight shot, no turns. Spectators watch the race from vehicles driving along each side of the track. There are no jockeys on the camels as they run. The camel owner or someone he has hired driving alongside the track controls a mechanical box on the camel’s back that has a whip to urge the camel along. So, imagine a passel of the most ungainly creatures God’s more humorous side was able to concoct arrayed in various bright colors loping along down a dirt track, flanked on either side by a menagerie of SUVs that are swerving in and out of one another and dodging lampposts, all while being driven onward by their robot jockeys and you’ll have camel racing.

See the robot there?

With all the forgoing about camels and time spent in the desert being said, I really spent most of my free time in Doha, which is quite the city. The city sits on the Eastern side of the country, right on the Persian Gulf. One morning I took a run along the Corniche, not far from my hotel, and snapped this picture:

It really is a beautiful city. And one of the cleanest ones I’ve visited in the Middle East. Not far from where I took that picture is Souq Waqif, a traditional-ish market (aka tourist trap. Still worth visiting though).

One of the things I enjoyed most about Souq Waqif was the animals. There was a certain part of the market for selling animals and I ran into some colorful specimens a time or two like these fellas:

Another interesting thing I learned about Qatari culture is that falcon hunting is a pretty big deal for a lot of the native Qataris. Once while walking through Souq Waqif, we came across this unique sight:

That’s right, a falcon hospital. You didn’t know there were hospitals for falcons? Where have you been living, under a rock? Or really anywhere in the world other than one of the Gulf countries? Cuz that seemed (seems) kinda crazy to me. But I did go inside and get to see some impressive looking birds, like this guy:

Just like horses and, apparently, camels, falcons can be extremely valuable, and their lineages are closely tracked. Add that to the list of hobbies I’ll never be rich enough to indulge in (right after camel racing. Super bummed about that one).

What really excited me though was running into these guys:

So, just in case you weren’t aware, I was pretty obsessed with horses when I was a kid. And I still think they’re remarkably beautiful animals. My favorite breed has always been Arabians. Down in Souq Waqif there are these ceremonial-type police guys going around, and their horses are just stunning. One evening I was walking around the souq and I came across the stables where they keep these horses:

It was a beautiful moment. The sun was just disappearing for the day, the last strains of the evening call to prayer still hung in the air, and this corral was tucked away from the bustle and noise of the rest of the souq. It was the kind of moment that brings to mind the word sublime.

In an attempt to expedite the capping off of an already exorbitantly long and disjointed, rambling post I’ll just put up these last few pictures with minimal exposition.

Have I ever mentioned I love food? If you’ve never eaten at a Yemeni restaurant you may want to reconsider your life priorities.

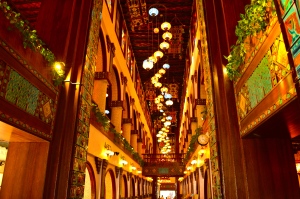

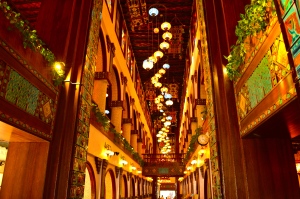

This was a place called al-Lu’lu’a (“The Pearl”). Before discovering oil in the Gulf area, one of the main drivers of the local economy was pearl diving. This place has nothing to do with pearl diving, but it was pretty.

One day I went swimming in the Persian Gulf. It was pretty cool.

This was a really cool art house I visited in Souq Waqif. There was some sweet art here I would have loved to buy, but, alas, I am poor.

One night I went to this Indian festival that was going on in Doha (yes, Indian as in people who are from India). Indian food is really good.

Qatar was a memorable experience. Ah shoot, I didn’t even get into mention meeting my roommate’s family at church in Doha or how his aunt hooked us up and got us into this one really sweet museum. And I’ve already started finishing up this post (well overdue) so I’m not gonna get into it. But that was really cool too. The world is a pretty cool place. People can be pretty cool. Life is pretty cool.